Tackling the loneliness epidemic: the role of the cafe

Across the Two Before Ten Group, we have roughly 1 million customer interactions each year. We view those social interactions as the most important thing we do. The exchange of coffee for money is just the enabling transaction. This prioritisation of social interaction guides everything we do within our organisation, from the way we design our stores, to the way we train our staff, and the economic decisions about how we will serve our customers. This blog aims to give you insight into why.

Australia, amongst other developed nations, is in the midst of a loneliness epidemic. The trend has been increasing steadily over the past decade, but the most recent few years of abrupt change and social distancing have tipped us into dangerous territory.

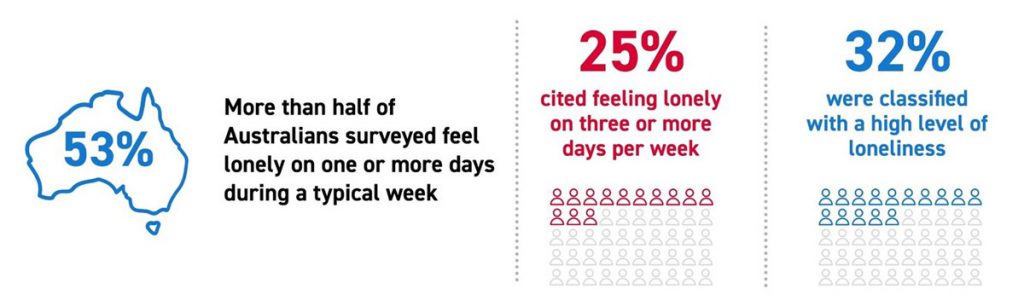

A report released this year revealed over 50% of Australians reported feeling lonely on one or more days during a typical week. As many as 1 in 3 are classified with a high level of loneliness, already up from 1 in 4 in 2020. The most at risk group were young, single people of whom 73% worryingly self-reported as regularly experiencing loneliness, yet only 36% were looking for ways to manage it.

The effects of loneliness on our health are far greater than psychological distress alone. Loneliness can be hard to describe, let alone recognise in ourselves or others. Britannica defines it as a distressing experience that occurs when a person’s social relationships are perceived by that person to be less in quantity, and especially in quality, than desired. The experience of loneliness is highly subjective; an individual can be alone without feeling lonely and can feel lonely even when with other people. The outcomes on quality of life and particularly physical health have often been overlooked. This is why it has become known as the silent killer.

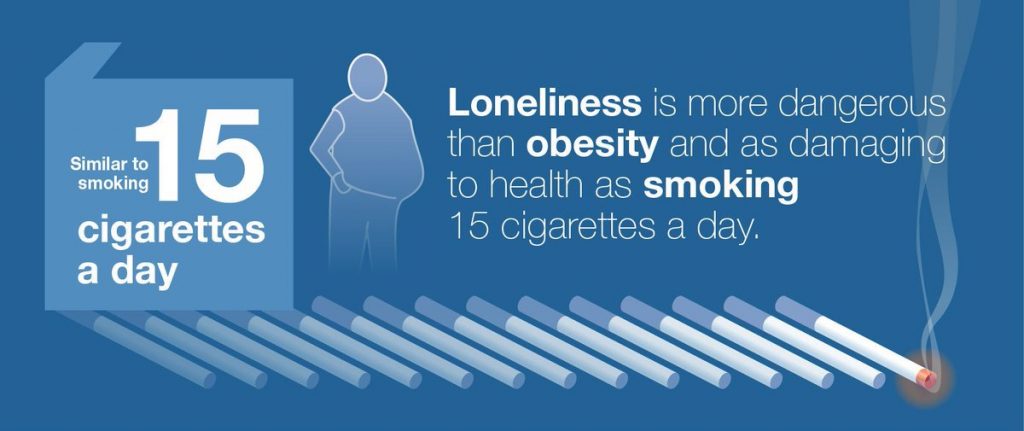

In medical studies, loneliness has been linked to weaker immune systems, higher blood pressure and even dementia. People who experience social isolation were associated with a 29% increased risk of heart attack and 32% greater risk of stroke. The effects on the cardiovascular system are equal or potentially even greater than smoking 15 cigarettes a day. It increases the risk of death more than such things as poor diet, obesity, alcohol consumption, and lack of exercise. Conversely, people with healthy social connections are 50% less likely to die prematurely.

There are very few health conditions so widespread amongst the population of our country yet so under recognised. Thankfully the issue is starting to be discussed more publicly. Federal MP Andrew Giles recently said, “I’m convinced we need to consider responding to loneliness as a responsibility of government.” Fiona Pattern MP has been calling for an Australian Minister for Loneliness, following in the footsteps of Britain who appointed their first in 2018. Accounting for the effects on loneliness through the government would mean that every new piece of social and economic legislation that comes into the parliament would have someone asking the question, “How does this impact people’s ability to connect with each other?”

The instigator for Britain’s addition of a Loneliness portfolio was MP Jo Cox who drove the initial work combating loneliness through a commission on the issue. In the UK, the majority of people over 75 live alone and about 200,000 older people in the UK have not had a conversation with a friend or relative in more than a month, according to government data. Most doctors in Britain see between one and five patients a day who have come mainly because they are lonely.

The difficulty of addressing an issue as big as this is not for the faint of heart. The ministerial position has already changed hands several times in only 4 years. In that time they’ve set up frameworks for social workers to prescribe activities and community groups, launched public health campaigns to reduce stigma, created a nationwide system of measuring loneliness and statistics, as well as boosting communities that provide social connection. Reducing loneliness on a national scale is a monumental task that the report acknowledged cannot be achieved by the federal government alone. It would require mayors, council leaders, public sector leaders, business leaders, employers, community and volunteer groups and everyday citizens to act on the issue as well.

The trouble is, there’s no easy fix to this epidemic. Loneliness has filtered into modern society through gradual changes that impact our daily lives in ways we couldn’t have predicted even a few decades earlier. Nowadays, multi-generational living has become a thing of the past as we strive towards the counterintuitive goal of living alone in our own place. This has had a detrimental effect on both the elderly and young adults – essentially any group of people that are not partnered up.

Technology has been a huge contributor to social isolation. It’s a common sight in restaurants, cafes, parks, and waiting rooms to see people’s full-undivided attention glued to their phone screen. Where once we spent idle time people watching or chatting with others, now we quickly turn to handheld devices for distraction. Social media, while initially touting the benefits of connection, has actually isolated us from one another. Broadcasting a polished, selective view of our lives over personal relationships.

Another aspect involves the drift towards migration and urbanisation. For the first time in history, the majority of the world’s population lives in cities. This may seem counterintuitive – how can we be lonelier amongst more people? Yet the feeling of being socially isolated is heightened when we are surrounded by people that we have no personal interaction with. In the past when most of the population lived in small neighbourhoods and villages, people grew up and lived their whole lives around a familiar group. These shared histories and small daily interactions with familiar faces formed the basis of a rich social life upon which friends and family were built. In this modern world where people move cities several times across a lifetime it can be a real challenge to both maintain close relationships and build new ones.

These days society is trending more and more towards automation and individual autonomy. This is reducing our opportunities to interact with other people in favour of efficiency, but to the detriment of our health. Where we once spoke to a staff member, now there is just a computer screen. Food is delivered to home by an app and shopping has moved online with parcels arriving at the door. We never realised how all these small increases in efficiency were reducing opportunities for communication and contributing in tiny increments to the loneliness of the general population.

The elimination of these daily interactions is simultaneously eroding away at our “third place”. A term coined by Ray Oldenburg in 1989, the third place describes a semi-public location between home (the first place) and work (the second place). During the industrial revolution the concept of a workplace that was separate from home developed as the economy shifted from farming to factory work. The local café gained popularity as a space located between home and work as a kind of community living room.

According to Oldenburg, the third place must be on neutral ground, be accessible and accommodating, have a playful mood, have conversation as the main activity and has a character derived from its regulars. It’s a venue for relaxation and connection with others in the community regardless of profession, social background or economic standing. The cafes of the 17th to 20th centuries were all this and more.

Before coffee was brought to Europe from the Arab world through the Ottoman Empire in the early 1600s, the third place was usually a church or the local pub. Water was unsafe to drink and ale or diluted wine was the beverage of choice. This left the general population mostly inebriated throughout their daily lives. Once coffee houses increased in popularity across England and France, this switch from alcohol to caffeine consumption changed society forever.

It was coffee houses that fuelled the Age of Enlightenment. People would come to these venues not only to drink, but primarily to socialise, debate and discuss topics of interest. The regulars of different coffee houses began to specialise in particular topics. Theologians and scholars would gather at one, stock brokers at another and sea-faring merchants at another. Anyone could distribute pamphlets or give a lecture to preach their passion. A drink was 2 pence and entry was 1 penny, leading to the term, “penny universities”.

Much of the Impressionist artwork serves as a historical snapshot of life during this period. Renoir’s painting Au Café suggests an environment that’s accessible to anyone who wished to visit, socialise and be seen. Later on in the USA, coffee houses served the Beat Generation as meeting places and performance spaces, creating an atmosphere conducive to a cultural movement promoting “alienation and place-bound estrangement from mainstream society”.

Cafes as a third space over the centuries have been a vital part of intellectual and societal advancement. Even more importantly they’ve served as a venue for social interaction and a safe place to build relationships. The semi-public space is an ideal environment to meet friends, colleagues or connect with strangers. “Having a coffee” is about more than just consuming a drink together. It implies an experience of meeting, discussion, catching up. The limited nature of meeting someone for coffee – how long it takes to consume a beverage or eat a pastry – facilitates interactions with people we may not know so well and aren’t yet comfortable inviting to our home. They are places to both foster old relationships and build new ones. The low cost of entry (the price of one drink) makes cafes accessible to the wider public, removing any trace of class or social hierarchy. It puts everyone on a level playing field. There are not many other institutions that are able to serve the same purpose in our communities.

At Two Before Ten, we believe utilising local cafes as the traditional third place is one way we can help address the loneliness epidemic. It’s the people you meet there, the regulars, the staff and the place itself that provides an environment for social interaction. The comfort of seeing familiar faces, the brief banter with wait staff and a barista who knows customers’ orders that all help you feel less isolated. It’s the reason why at Two Before Ten we will never use apps to pre-order coffee, or QR codes to order at the table. It’s why we continue to provide full table service when other cafés are phasing it out due to staff costs. We know that the 1 million customer interactions we have every year are opportunities to make people feel more connected. It’s why our venues are packed full of booths, bench seats and quiet nooks and crannies. There must be enough space for friends and community to connect – and stay as long as they need.

As our world carries us towards greater isolation, we hope to always be here to bring people together and allow them to connect in a more human way.