From tree to cup | The coffee farming process

Coffee is one of the world's most traded commodities. For Australians in particular, a cup of coffee is an integral part of most people's daily life. However, the process of getting coffee beans grown on the opposite ends of the earth into our cups is not a simple one. Coffee beans must first go through the process of harvesting, processing, sorting, export, roasting, grinding and brewing before finally ending up as a shot of espresso. If you've ever been curious about what goes on behind the scenes, or wanted to know if growing your own coffee would be possible, this article is for you.

Growing coffee trees

The vast majority of the world's coffee is grown inside the earth's equatorial zone. It's within this zone that the right environmental conditions exist to support optimal growth of coffee trees. In the case of Arabica coffee, the right conditions include high rainfall, well-drained soil, high humidity, a consistent temperature of 18-24 degrees Celsius and ample sunshine. This typically means steep plantations at an altitude over 1000 MASL within a tropical climate.

The original coffee trees grew in the shade or dappled sunlight and are considered an understory plant. Shade-grown coffee today is usually sweeter and less prone to pests, but produces a lower yield, which is a compromise farmers don't always choose.

There are now hundreds of varieties of Arabica coffee available for farmers to choose from. Many are naturally occurring hybrids and some are lab-created. Farmers generally favour a handful of varietals that have been developed specifically for their region. Some of the most well known varietals include Typica, Bourbon, Gesha, Caturra and Pacamara.

Coffee trees take 2-5 years before bearing fruit, and only remain productive up to around 20 years. This means a constant cycle of pruning, fertilising, growing seedlings and replanting. Five years can be a long time to wait for a return for many low-income farmers. Especially with the chance of ruin from pests and disease ever present.

Harvesting coffee cherries

The harvest process is incredibly labour intensive. Most of the world's coffee is hand picked and therefore only financially viable in developing countries. Coffee cherries grow along their tree branches in clusters, ripening at different times across several weeks. One branch could have fruit at 4 different stages of ripeness from green to yellow to red to burgundy.

For commercial grade, supermarket or instant coffee, pickers will strip pick - removing all cherries from the tree regardless of whether they are ripe or not. This is all about quantity over quality. Specialty grade coffee requires pickers to be very specific, picking only the cherries of a particular colour. Some coffee farms even use coloured wristbands for pickers to compare the optimum colour.

Coffee bean processing and fermentation

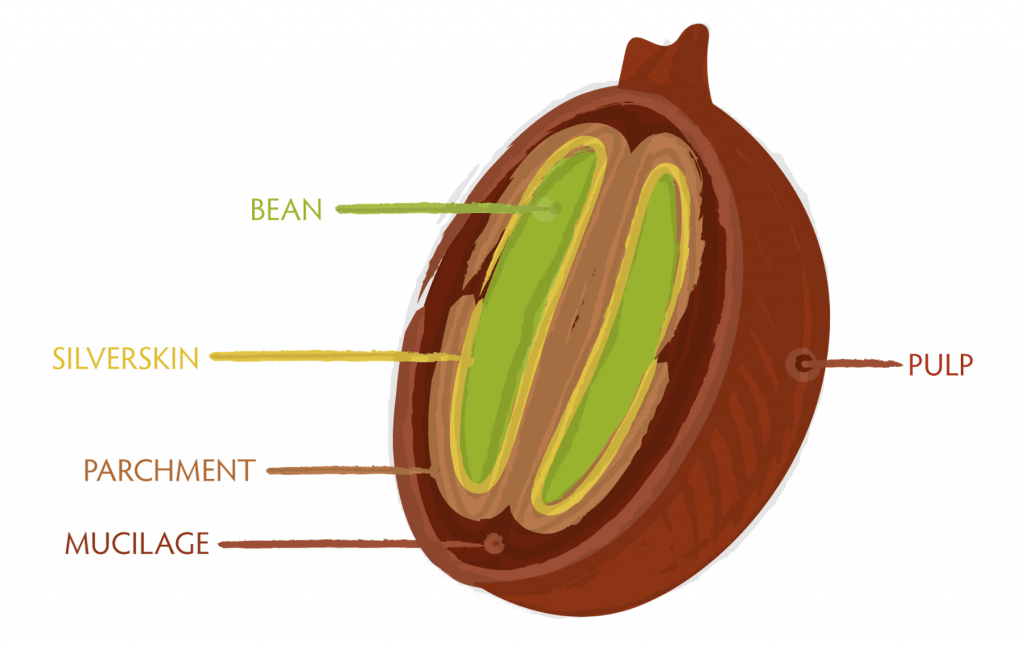

What we know as coffee beans are actually the seeds of the coffee cherry - usually two seeds per cherry. Once the cherries have been picked they need to be processed as fast as possible to avoid spoilage. There are several steps that go into processing coffee, with two different ways being the most typical.

Washed (wet) process

The washed coffee process is the most widely used, and is the fastest option. A washed coffee is often described as being more "clean" in flavour. It also requires more equipment and loads of water. Most coffee farmers who use this process method send their cherries off to a local wet mill. There, their harvests will be combined with all the other fruit from surrounding farms. In some cases the farmers themselves, in the form of a co-op, own these wet mills.

The first step in the washed coffee process is placing the coffee cherries in vats of water. Defective cherries will float while high quality cherries will sink. The floaters are removed and processed separately as commercial grade. Then farmers will remove the fruit using a pulping machine. This separates the skin and pulp from the bean, but still leaves the mucilage and parchment attached to the seed.

Next comes the fermentation stage. The beans are stored in tanks where microorganisms within the beans create enzymes responsible for breaking down the mucilage. Fermentation usually takes 24 hours or less, but some producers have started experimenting with extended fermentation techniques.

Afterwards, drying is done either with mechanical dryers or under the sun on patios or raised beds until the beans reach approximately 12% moisture. They might then be stored in sacks for a while before going through a coffee huller machine, which removes the "parchment" layer from the coffee beans.

Natural (dry) process

Naturally processed coffee is the traditional, age-old method. It's ideal for drier climates and small producers, as less equipment is required. The dry method can be less consistent and usually results in coffee with stronger fruity flavours.

Coffee that's processed naturally is sun dried on patios or raised beds with the cherry still surrounding the seeds, allowing fermentation to happen at the same time as drying. During the day workers will turn the fruit so it dries evenly. Then they will cover with tarps at night to protect from rain. This can go on for several weeks.

By the time the cherries have reached 10-12% moisture they will be rock hard and can be sent through the hulling machine to remove the dried pulp and hulls at the same time.

Decaf coffee process

Decaffeinated coffee undergoes a further process to remove most of the caffeine. You can read more about how decaf is made on our previous blog post.

Sorting and grading

Now the coffee beans are dry and have had all the pulp and parchment removed. But they still need to undergo sorting. A variety of machines can be used for this, separating beans by screen size, weight, density, colour and defects. Some machines blow puffs of air, some shake beans through sieves, and one in particular utilises gravity with a tilted table that pulses and vibrates beans into bins on separate sides.

Afterwards, hand sorting is done to remove defects missed by the machines. This work is typically done by women. Specialty coffee is almost always "hand-cleaned" and the same beans can be sorted 2 or 3 times by different workers.

Differing origins and varietals get scored on a range of criteria. This includes size, number of defects, moisture levels and a grade system which rates aroma, flavour, aftertaste, acidity, body, balance, uniformity, clean cup, sweetness and overall. The final score determines whether a coffee is exchange (commercial), premium or specialty grade. Q graders are the coffee equivalent of wine sommeliers and must go through rigorous testing to achieve certification.

Exporting from the tropics to the rest of the world

At this stage, we call the raw coffee beans "green beans". Green bean buyers travel the world in search of high quality coffee. They work with farmers to improve growing and processing techniques, taste a huge variety of coffees (using a worldwide standard called "cupping") and negotiate prices. Ethical buyers usually set up long-term contracts with farmers or co-ops. This gives both parties some security and predictability of demand for future harvests.

When deals are made, large sacks of coffee green beans are sealed and loaded into shipping containers for export. Months later, upon reaching Australia, they're stored in warehouses ready to send out to coffee roasters across the country who have pre-ordered beans the sack or tonne.

Roasting coffee

When the coffee beans finally arrive at the roastery it will already have been up to 6 months or more since harvest. After around 12 to 18 months the flavour of the green beans starts to degenerate and roasting becomes more difficult. It's important that coffee roasters plan well in advance to make sure they have just the right amount of green beans available when needed.

Small and medium scale roasteries often use roasting machines that can handle around 5kg to 20kg of beans per batch. Larger scale roasteries utilise machines much larger, with 50kg or more capacities and an almost fully automated process. Roasting in smaller batches allows more flexibility and finesse. A 7kg batch of coffee beans can be adjusted and modified throughout the roast. Based on how the beans are responding to conditions in weather, age, humidity, etc.

To roast a batch of coffee, the roaster will load a set weight into the pre-heated machine's hopper and then open the gate to let them fall into the rotating drum once it's at the optimum temperature. Roasting software is connected to temperature probes, which allows them to follow roast curves and modify the machine's heat or airflow in response. Certain goals must be reached for consistency between batches, such as hitting "first crack" at a particular time and "dropping" the batch after the right amount of development. The beans are then rapidly cooled by fans to stop further development.

There are an immeasurable number of variables that can be changed when roasting coffee. A new origin will often take lots of experimentation to find an ideal roast curve to highlight the desired flavours for its intended purpose.

Once the coffee beans have finished roasting they will be around 50% larger and 15% lighter than their previous green bean state. This is due to moisture loss and changes to cell structure. Different origins will be combined to create coffee blends, then packaged and delivered to cafes.

Brewing coffee

This is the part most people are familiar with, as it happens right in front of us at the cafe. Every morning, whole coffee beans are loaded into the hoppers and freshly ground for each coffee. Baristas fill the portafilters with a precise dose of ground coffee at a very particular grind size. These are called "recipes" and are formulated based on the purpose, flavours and freshness of each blend or single origin. Small changes can mean under or over extracted coffee. So it's important that baristas time and taste their brews throughout the day for consistency.

The final cup

Throughout the entire process, from the coffee farm to the final cup, the quantity of coffee produced is only a small fraction of what it began as. After removing the fruit, the hulls, the moisture, the defects, the too-small beans, the moisture again, then extracting through water; the final shot of espresso will only be 2% of its original biomass. In fact, to support a coffee habit of just one cup a day, every person would need 6 coffee trees. While coffee is an essential part of our daily lives, it is also something to be thankful for and a huge benefit of our globalised system of trade.